It’s time again for Six Degrees of Separation, a monthly link-up hosted by Kate at Books Are My Favourite and Best. Each month a book is chosen as a starting point and linked to six other books to form a chain. A book doesn’t need to be connected to all the other books on the list, only to the one next to it in the chain.

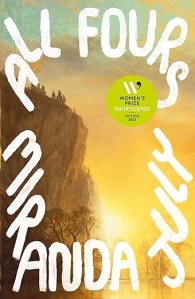

This month we start with All Fours by Miranda July, shortlisted for the Women’s Prize for Fiction 2025 and several other awards. I haven’t read it and probably won’t. This is Amazon’s description:

A semi-famous artist turns forty-five and gives herself a gift – a cross-country road trip from LA to New York, without her husband and child. But thirty minutes after setting off, she spontaneously exits the freeway, beds down in a nondescript motel – and embarks on the journey of a lifetime.

Miranda July’s second novel confirms the brilliance of her unique approach to fiction. With July’s wry voice, perfect comic timing, unabashed curiosity about human intimacy, and palpable delight in pushing boundaries, All Fours tells the story of one woman’s quest for a new kind of freedom. Part absurd entertainment, part tender reinvention of the sexual, romantic, and domestic life of a forty-five-year-old female artist, All Fours transcends expectation while excavating our beliefs about life lived as a woman. Once again, July hijacks the familiar and turns it into something new and thrillingly, profoundly alive.

First link: I have read another book that was shortlisted for the previous year’s Women’s Prize for Fiction – Restless Dolly Maunder by Kate Grenville.

Dolly Maunder is born at the end of the 19th century, when society’s long-locked doors are just starting to creak ajar for determined women. Growing up in a poor farming family in rural New South Wales, Dolly spends her life doggedly pushing at those doors. A husband and two children do not deter her from searching for love and independence.

This is the fictionalised life story of Kate Grenville’s maternal grandmother, Sarah Catherine Maunder, known as Dolly. She was not only restless but also clever and determined – she knew what she wanted and she did her best to achieve it.

Second link: One of my favourite books by Kate Grenville is One Life: My Mother’s Story, her biography of Nance Russell, based on Nance’s memories, making it much more than a factual account of a person’s life. It’s a book that casts light not only on Nance’s life but also on life in Australia for most of the 20th century. Nance was born in 1912 and died in 2002, so she lived through two World Wars, an economic depression and a period of great social change. Nance wasn’t famous, the daughter of a rural working-class couple who became pub-keepers, but she was a remarkable woman.

It’s a vivid portrait of a real woman, a woman of great strength and determination, who had had a difficult childhood, who persevered, went to University, became a pharmacist, opened her own pharmacy, brought up her children, and helped build the family home. She faced sex discrimination and had to sell her pharmacy in order to look after her children at home.

Third link: Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China by Jung Chang, a family memoir – the story of three generations of women in Jung Chang’s family – her grandmother, mother and herself, telling of their lives in China up to and during the years of the violent Cultural Revolution. Her family suffered atrociously, her father and grandmother both dying painful deaths and both her mother and father were imprisoned and tortured. She casts light on why and how Mao was able to exercise such paralysing control over the Chinese people. His magnetism and power was so strong and coupled with his immense skill at manipulation and his ability to inspire fear, it proved enough to subdue the spirit of most of the population; not to mention the absolute cruelty, torture and hardships they had to endure.

My fourth link moves from a memoir to crime fiction in Death of a Red Heroine by Qiu Xiaolong, the first book featuring Chief Inspector Chen. Chen is a reluctant policeman, he has a degree in English literature and is a published poet and translator. This is as much historical fiction as it is crime fiction. There is so much in it about China, its culture and its history before 1990 – the Communist regime and then the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s – as well as the changes brought about in the 1990s after the massacre of Tiananmen Square. This does interfere with the progress of the murder investigation as Chen has to cope with the political ramifications and consequently there are several digressions and the pace is slow and lacking tension. As Chen is a poet as well as a policeman there are also references to Chinese literature.

Fifth link: Another fictional Chief Inspector who writes poetry is Adam Dalgleish in The Murder Room by P D James. The Murder Room itself is in the Dupayne Museum, displaying the most notorious murder cases of the 1920s and 30s, with contemporary newspaper reports of the crimes and trials, photographs and actual exhibits from the scenes of the murders. These were actual crimes and not fictional cases made up by P D James.

The novel begins, as Adam Dalgleish visits the Dupayne in the company of his friend Conrad Ackroyd who is writing a series of articles on murder as a symbol of its age. A week later the first body is discovered at the Museum and Adam and his colleagues in Scotland Yard’s Special Investigation Squad are called in to investigate the killing, which appears to be a copycat murder of one of the 1930s’ crimes.

Another crime fiction writer with the surname James is my sixth link: Sausage Hall by Christina James, the third novel in the DI Yates series. It has a sinister undercurrent exploring the murky world of illegal immigrants, and a well researched historical element. It’s set in the South Lincolnshire Fens and is an intricately plotted crime mystery, uncovering a crime from the past whilst investigating a modern day murder. Sausage Hall is home to millionaire Kevan de Vries, grandson of a Dutch immigrant farmer. I liked the historical elements of the plot and the way Christina James connects the modern and historical crimes, interwoven with the history of Kevan’s home, Laurieston House, known to the locals as ‘Sausage Hall’ and the secrets of its cellar.

My chain is made up of novels shortlisted for the Women’s Prize for Fiction, a biography, a memoir and three murder mysteries. It travels from New York to the UK via Australia and China.

Where does your chain end up, I wonder?

Next month (July 5, 2025), we’ll start with the 2025 Stella Prize winner, Michelle de Kretser’s work of autofiction, Theory & Practice.