Spell the Month in Books is a linkup hosted by Jana on Reviews From the Stacks on the first Saturday of each month. The goal is to spell the current month with the first letter of book titles, excluding articles such as ‘the’ and ‘a’ as needed. That’s all there is to it! Some months there are optional theme challenges, such as “books with an orange cover” or books of a particular genre, but for the most part, any book you want to use is fair game!

The theme this month is a Freebie and I’m featuring books I’ve recently acquired and books I read before I started my blog, so I haven’t reviewed any of them and have linked the titles to the descriptions on Amazon.

F is for Forty Rules of Love by Elif Shafak, fiction.

Enlightening, enthralling. An affecting paean to faith and love (Metro), fiction.

E is for Every Body Should Know This: The Science of Eating for a Lifetime of Health by Dr. Federica Amati, Medical Scientist and Head Nutritionist at ZOE, nonfiction.

‘Dr Federica is a human encyclopaedia when it comes to the science of food and health. This book contains the most critical answers to nutrition that we’ve all been searching for. A must read’– Steven Bartlett

B is for The Bull of Mithros by Anne Zouroudi, crime fiction.

‘A cracking plot, colourful local characters and descriptions of the hot, dry countryside so strong that you can almost see the heat haze and hear the cicadas – the perfect read to curl up with’― Guardian

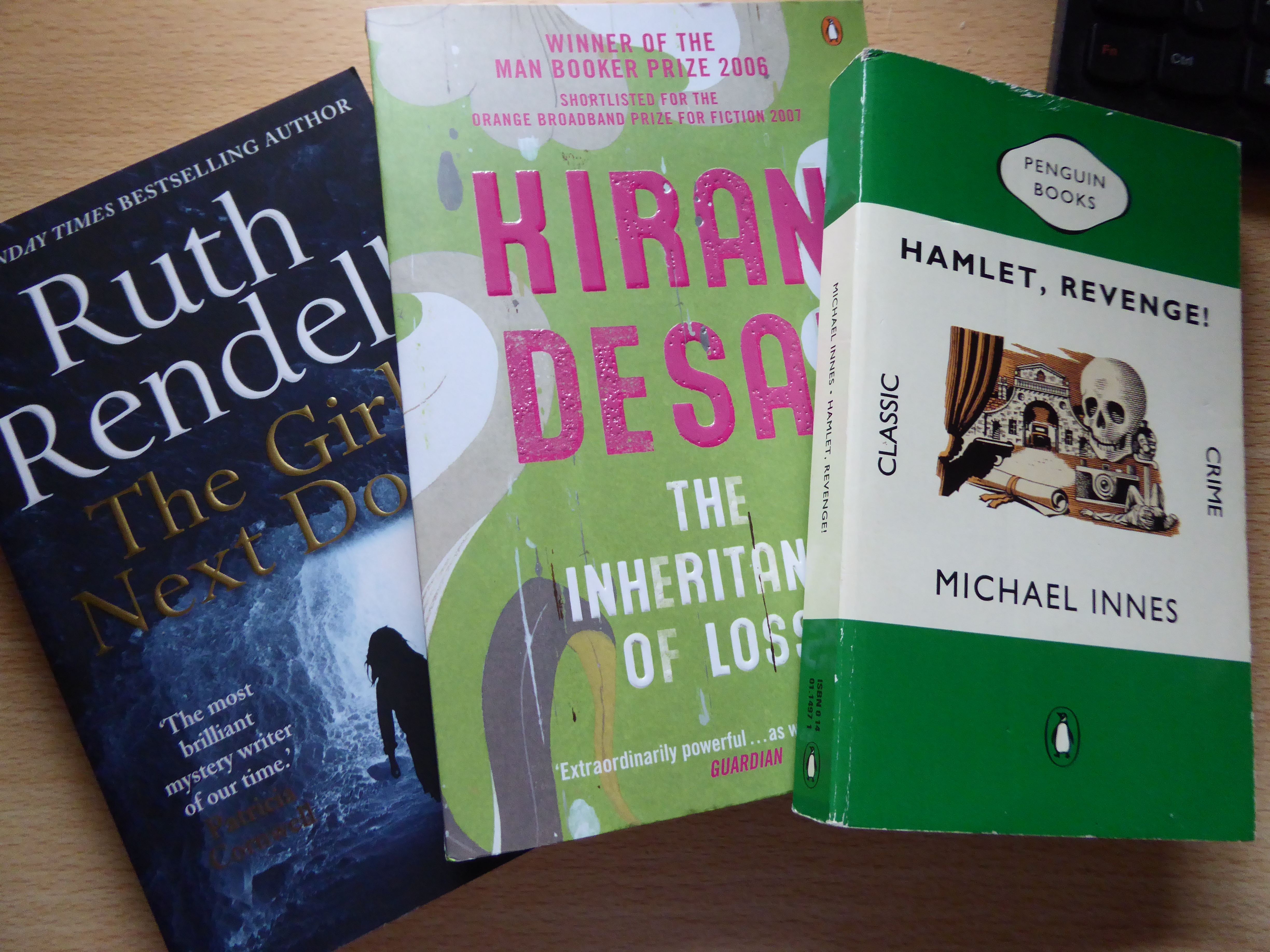

R is for Road Rage by Ruth Rendell, crime fiction.

‘With immaculate control, Ruth Rendell builds a menacing crescendo of tension and horror that keeps you guessing right up to the brilliantly paced finale’― Good Housekeeping

U is for Under the Greenwood Tree by Thomas Hardy, fiction.

Set in the small village of Mellstock in Thomas Hardy’s fictional Wessex, this is both a love story and a nostalgic study into the disappearance of old traditions and a move towards a more modern way of life. (Amazon)

A is for As a Jew: Reclaiming Our Story from Those Who Blame, Shame, and Try to Erase Us by Sarah Hurwitz, nonfiction.

‘This book explains antisemitism and the danger it poses—not just to Jews, but to all of us. It also reveals the breathtaking history and resilience of the Jewish people and the beauty of Jewish tradition’ – Van Jones, CNN Host and New York Times bestselling author

R is for The Return of the Soldier by Rebecca West, fiction.

Returning to his stately English home from the chaos of World War I, a shell-shocked officer finds that he has left much of his memory in the front’s muddy trenches. (Amazon)

Y is for The Years by Virginia Woolf, fiction.

Published in 1937, this was Virginia Woolf’s most popular novel during her lifetime. It’s about one large upper-class London family, spanning three generations of the Pargiter family from the 1880s to the 1930s. (Amazon)

The next link up will be on March 7, 2026 take your pick from Pi Day, March Madness, or Green Covers.