This is a monthly link-up hosted by Kate at Books Are My Favourite and Best. On the first Saturday of every month, a book is chosen as a starting point and linked to six other books to form a chain. Readers and bloggers are invited to join in by creating their own ‘chain’ leading from the selected book.

Books can be linked in obvious ways – for example, books by the same authors, from the same era or genre, or books with similar themes or settings. Or, you may choose to link them in more personal ways: books you read on the same holiday, books given to you by a particular friend, books that remind you of a particular time in your life, or books you read for an online challenge.

A book doesn’t need to be connected to all the other books on the list, only to the ones next to them in the chain.

This month we are starting with We Have Always Lived in the Castle by Shirley Jackson is a fantastic book; a weirdly wonderful book about sisters, Merricat and Constance. They live in a grand house, away from the village, behind locked gates, feared and hated by the villagers. Merricat is an obsessive-compulsive, both she and Constance have rituals that they have to perform in an attempt to control their fears. Merricat is a most unreliable narrator.

I’m starting my chain with The Lottery is a short story also written by Shirley Jackson. It was first published on June 25, 1948, in The New Yorker, (the link takes you to the story.) The lottery is an annual rite, in which a member of a small farming village is selected by chance. This is a creepy story of casual cruelty, which I first read several years ago. The shocking consequence of being selected in the lottery is revealed only at the end.

The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie by Muriel Spark, was first published in The New Yorker magazine on 14th October 1961. It is perhaps Muriel Spark’s most famous novel about the ‘Brodie set’. But which one of them causes her downfall and her loss of pride and self-absorption? What really impresses me about this book is the writing, so compact, so perceptive and so in control of the shifts in time backwards and forwards. It’s a joy to read.

Another book that was a joy to read is Miss Austen by Gill Hornby. This is the untold story of the most important person in Jane’s life – her sister Cassandra. After Jane’s death, Cassandra lived alone and unwed, spending her days visiting friends and relations and quietly, purposefully working to preserve her sister’s reputation. Cassandra is convinced that her own and Jane’s letters to Eliza Fowle, the mother of Cassandra’s long-dead fiancé, are still somewhere in the vicarage. Eventually she finds the letters and confronts the secrets they hold, secrets not only about Jane but about Cassandra herself. Will Cassandra reveal the most private details of Jane’s life to the world, or commit her sister’s legacy to the flames?

My next link is also a book in which letters play a key part. It’s The ABC Murders by Agatha Christie, a Golden Age of Detective Fiction novel first published in 1936. A series of murders are advertised in advance in letters to Poirot, and signed by an anonymous ‘ABC’. An ABC Railway guide is left next to each of the bodies. So the first murder is in Andover, the victim a Mrs Alice Ascher; the second in Bexhill, where Betty Barnard was murdered; and then Sir Carmichael Clarke in Churston is found dead. The police are completely puzzled and Poirot gets the victims’ relatives together to see what links if any can be found. Why did ABC commit the murders and why did he select Poirot as his adversary?

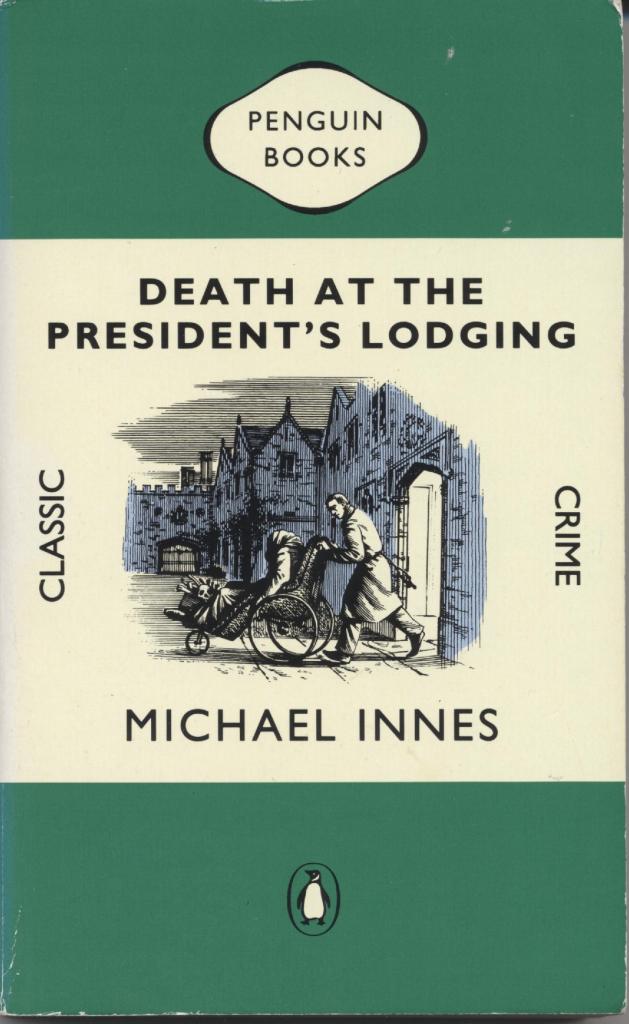

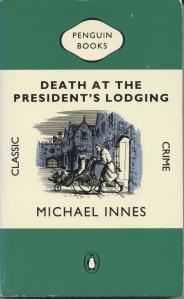

Another Golden Age murder mystery published in 1936 is Death at the President’s Lodging by Michael Innes. This is essentially a ‘locked room’ mystery. Dr Umpleby, the unpopular president of St Anthony’s College (a fictional college similar to an Oxford college) is found in his study, shot through the head. His head was swathed in a black academic gown, a human skull beside his body and surrounding it, little piles of human bones. Inspector Appleby from Scotland Yard is in charge of the investigation, helped by Inspector Dodd from the local police force.

Innes’s writing is intellectual, detailed, formal and scattered with frequent literary allusions and quotations. The plot is complex and in the nature of a puzzle. There are plenty of characters, the suspects being the dons of the college.

And my final link is Ryan’s Christmas by L J Ross, another ‘locked room mystery’. DCI Ryan, and DS Phillips and their wives are stranded in Chillingham Castle when a snowstorm forces their car off the main road and into the remote heart of Northumberland. Cut off from the outside world by the snow, with no transport, mobile signals or phone lines they join the guests who had booked a ‘Candlelit Ghost Hunt’. Then Carole Black, the castle’s housekeeper is found dead lying in the snow, stabbed through the neck. There’s only one set of footpaths in the snow, and those are Carole’s, so who committed the murder?

My chain includes books by the same author, books first published in the same magazine, letters, Golden Age murder mysteries, and ‘locked room’ mysteries.

‘Next month (December 6, 2025), we’ll start with a novella that you may read as part of this year’s Novellas in November – Seascraper by Benjamin Wood.

I’m currently reading Death at the President’s Lodging – a used Penguin Books edition published in 1958, one of the green and white crime fiction books.

I’m currently reading Death at the President’s Lodging – a used Penguin Books edition published in 1958, one of the green and white crime fiction books.