‘When you play the game of thrones, you win or you die. There is no middle ground.’

When we began watching the HBO TV series, A Game of Thrones, I was hooked and once we finished watching I immediately wanted to read the series, A Song of Fire and Ice. I’d just read The Sunne in Splendour by Sharon Penman, about the Wars of the Roses and had noticed the similarities between that and A Game of Thrones, the battles between the Houses of York and Lancaster paralleled by those between the Houses of Stark and Lancaster for example.

I don’t often read a book after seeing an adaptation, but in this case it proved ideal – the actors and scenery were perfect for my reading of the book, although there are some differences (the ages of the Stark children for example). I loved both the book and the TV series.

Blurb:

Summers span decades. Winter can last a lifetime. And the struggle for the Iron Throne has begun.

As Warden of the north, Lord Eddard Stark counts it a curse when King Robert bestows on him the office of the Hand. His honour weighs him down at court where a true man does what he will, not what he must ‘¦ and a dead enemy is a thing of beauty.

The old gods have no power in the south, Stark’s family is split and there is treachery at court. Worse, the vengeance-mad heir of the deposed Dragon King has grown to maturity in exile in the Free Cities. He claims the Iron Throne.

I was completely immersed in this world inhabited by numerous characters and set in different locations (Seven Kingdoms), all portrayed in meticulous detail and expertly constructed so that all the fantastic creations are credible, and complete with back stories and histories. Beginning with a Prologue the book is then narrated through different characters’ points of view – each chapter is headed by that character’s name making the plotlines easy to follow:

- Lord Eddard “Ned” Stark, Warden of the North and Lord of Winterfell, Hand of the King.

- Lady Catelyn Stark, of House Tully, wife of Eddard Stark.

- Sansa Stark, elder daughter of Eddard and Catelyn Stark.

- Arya Stark, younger daughter of Eddard and Catelyn Stark.

- Bran Stark, second-youngest son of Eddard and Catelyn Stark.

- Jon Snow, illegitimate son of Eddard Stark, mother unknown.

- Tyrion Lannister, son of Lord Tywin Lannister, called the Imp, a dwarf, brother of the twins, the beautiful and ruthless Queen Cersei and Ser Jaime, called the Kingslayer,

- Daenerys Targaryen, Stormborn, the Princess of Dragonstone, sister of Prince Viserys, the last of the Targaryens.

Other characters include:

- King Robert of the House Baratheon, Lord of the Seven Kingdoms, Eddard Stark’s oldest friend, married to Queen Cersei, his son Joffrey, spoiled and wilful with an unchecked temper, heir to the Iron Throne.

- Robb Stark, oldest true born son of Eddard Stark. He remained at Winterfell when Eddard became the Hand of the King.

- Tywin Lannister, Lord of Casterly Rock, Warden of the West, Shield of Lannisport.

- Khal Drogo – a powerful warlord of the Dothraki people on the continent of Essos, a very tall man with hair black as midnight braided and hung with bells.

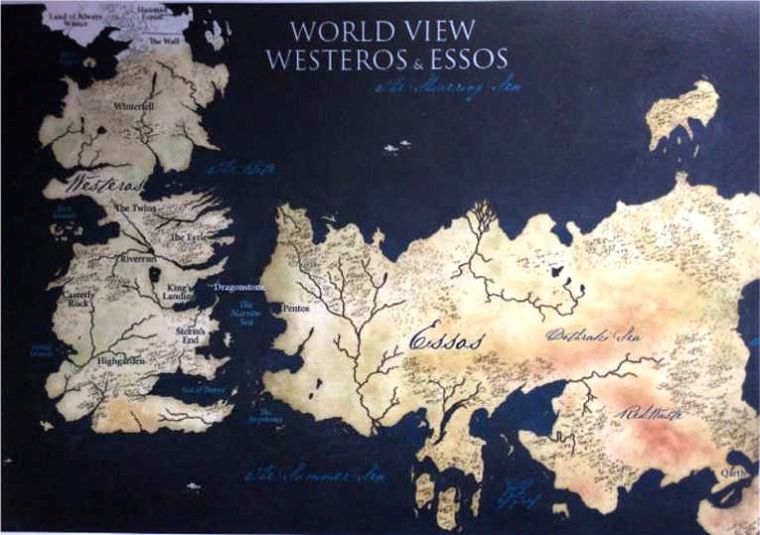

Locations:

- Winterfell: the ancestral castle of House Stark.

- The Wall: built of stone, ice and magic, on the northern border of the Seven Kingdoms, guarded by the Night’s Watch to protect the Kingdoms from the dangers behind the huge wall from ‘the Others’ and the Wildings.

- Beyond the Wall: the first book begins Beyond the Wall with members of the Night’s Watch on the track of a band of Wildling raiders.

- King’s Landing: a walled city, the capital of the continent of Westeros and of the Seven Kingdoms.

- Essos: across the Narrow Sea from Westeros, includes the grassland known as the Dothraki Sea.

This article in The Telegraph lists the locations used in the TV series.

This is no fairy tale – it’s set in a grim and violent world full of tragedy, betrayals and battles; a tale of good versus evil in which family, duty, and honour are in conflict, the multiple viewpoints giving a rounded view of the conflicts the characters face. It’s a love story too. There are knights, soldiers and sorcerers, priests, direwolves, giants, assassins and bastards. It’s complex and multifaceted, and it’s full of stories and legends – here for example Maester Luwin tells young Bran Stark about the children of the forest:

“They were people of the Dawn Age, the very first before kings and kingdoms,” he said. “In those days there were no castles or holdfasts, no cities, not so much as a market town to be found between here and the sea of Dorne. There were no men at all. Only the children of the forest dwelt in the lands we now call the Seven Kingdoms.

‘They were a people dark and beautiful, small of stature, no taller than children even when grown to manhood. They lived in the depths of the wood, in caves and crannogs and secret tree towns. Slight as they were, the children were quick and graceful. Male and female hunted together, with weirwood bows and flying snares. Their gods were the gods of the forest, stream and stone, the old gods whose names are secret. Their wisemen were called greenseers and carved strange faces in the weirwoods to keep watch on the woods. (page 713)

I shall be reading the next book in the series soon, A Clash of Kings. The other books are A Storm of Swords, A Feast for Crows, and A Dance with Dragons.

I read the Kindle Edition:

- File Size: 8515 KB

- Print Length: 819 pages

- Page Numbers Source ISBN: 0007448031

- Publisher: Harper Voyager (23 Dec. 2010)

Reading Challenges: Mount TBR Reading Challenge – a book I’ve had since October 2015, and the What’s In a Name Challenge – in the category of a book with a piece of furniture in the title.

For me the book chosen for the current Classics Club Spin is The Man Who Would Be King by Rudyard Kipling. It’s a novella, just 60 pages, which first appeared in The Phantom Rickshaw and other Eerie Tales, published in 1888.

For me the book chosen for the current Classics Club Spin is The Man Who Would Be King by Rudyard Kipling. It’s a novella, just 60 pages, which first appeared in The Phantom Rickshaw and other Eerie Tales, published in 1888.

Inspector Alan Grant investigates the apparent suicide of a young and beautiful film star, Christine Clay, who was found dead beneath the cliffs of the south coast. But he soon discovers that was in fact murder as a coat button was found twisted in her hair and he suspects a young man, Robin Tisdall who had been staying with Christine in a remote cottage near the beach, especially when it is revealed that she has named him as a beneficiary in her will. Tisdall has lost his coat and so the search is on to find it to prove either his innocence or guilt.

Inspector Alan Grant investigates the apparent suicide of a young and beautiful film star, Christine Clay, who was found dead beneath the cliffs of the south coast. But he soon discovers that was in fact murder as a coat button was found twisted in her hair and he suspects a young man, Robin Tisdall who had been staying with Christine in a remote cottage near the beach, especially when it is revealed that she has named him as a beneficiary in her will. Tisdall has lost his coat and so the search is on to find it to prove either his innocence or guilt.

Fry, who for a while had an affair with Vanessa Bell, Virginia’s sister, was a friend of Virginia’s. She wrote three books subtitled ‘A Biography‘ – her

Fry, who for a while had an affair with Vanessa Bell, Virginia’s sister, was a friend of Virginia’s. She wrote three books subtitled ‘A Biography‘ – her