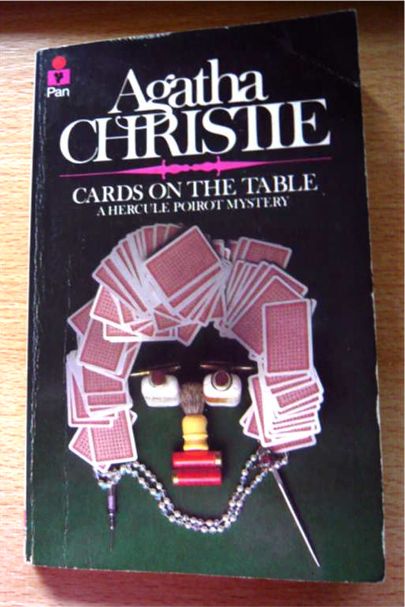

I think Cards on the Table is one of the best of Agatha Christie’s books. It was first published in 1936 and has been reprinted many times since then. My copy is a Pan Books edition published in 1951 with this cover:

From the back cover:

Mr Shaitana is a collector. He collects snuff boxes, Egyptian antiquities … and … murderers.

His murderers are of the very finest. Not the second rate individuals who are caught and convicted. Delighting in his role as a modern Mephistopheles, Shaitana gathers his four murderers for an evening of cards.

Before the evening ends, Mr Shaitana will himself be a murder victim. How very fortunate that he invited a fifth guest to his gathering, M. Hercule Poirot.

One of the things that pleased me about this book is Agatha Christie’s Foreword in which she states that it is not the sort of detective story where the least likely person is the one to have committed the crime. This story has just four suspects and any one of them ‘given the right circumstances‘ might have committed the crime. She goes on to explain that there are four distinct types, the motives are peculiar to each person and each would employ a different method. She concludes:

The deduction must, therefore, be entirely psychological, but it is none the less interesting for that, because when all is said and done it is the mind of the murderer that is of supreme interest.

All of which suits Poirot down to the ground as he considers the psychology of each of the four suspects, Dr Roberts, a very popular doctor who may have killed a patient or two, Mrs Lorimer, a first-class bridge player and a widow who husband died under suspicious circumstances, Major Despard, a daring character, an explorer who possibly killed a botanist whilst on an expedition up the Amazon, and Anne Meredith, a young woman, a timid and careful bridge player, who may have poisoned her employer.

Poirot is not on his own, also at the bridge party were Superintendent Battle, a stolid officer from Scotland Yard (he first appeared in The Secret of Chimneys), Colonel Race, a Secret Service agent (he first appeared in The Man in the Brown Suit), and Mrs Ariadne Oliver, writer of popular detective fiction, (meeting Poirot for the first time). It helps if you can play bridge to understand how Poirot uncovered the murderer, but it’s not necessary – I managed with just a minimal memory of the card game, and it all hinges on the psychology of the characters anyway.

As Ariadne Oliver is used by Agatha Christie to convey some of her own opinions I wondered whether this description of her physical appearance was how she viewed herself:

… she was an agreeable woman of middle age, handsome in a rather untidy fashion with fine eyes, substantial shoulders and a large quantity of rebellious grey hair with which she was continually experimenting. One day her appearance would be highly intellectual – a brow with the hair scraped back from it and coiled in a large bun in the neck – on another Mrs Oliver would suddenly appear with Madonna loops, or large masses of slightly untidy curls. On this particular evening Mrs Oliver was trying out a fringe. (page 13)

I think there is no doubt that Ariadne’s views on writing and on the character of her detective are Agatha Christie’s own views. For ‘Finn’ in the extract quoted below read ‘Belgian’:

… I regret only one thing – making my detective a Finn. I don’t really know anything about Finns and I’m always getting letters from Finland pointing out something impossible that he’s said or done. (page 55)

And this must be from her own experience too:

I’m always getting tangled up in horticulture and things like that. People write to me and say I’ve got the wrong flowers all out together. As though it mattered – and, anyway, they are all out together in a London shop. (page 110)

And this about writing?:

One actually has to think, you know. And thinking is always a bore. And you have to plan things. And then one gets stuck every now and then, and you feel you’ll never get out of the mess – but you do! Writing’s not particularly enjoyable. It’s hard work, like everything else. …

Some days I can only keep going by repeating over and over to myself the amount of money I might get for my next serial rights. That spurs me on, you know. So does your bank-book when you see how much overdrawn you are. …

‘I can always think about things,’ said Mrs Oliver happily. ‘What is so tiring is writing them down. I always think I’ve finished, and then when I count up I find I’ve only written thirty thousand words instead of sixty thousand, and so then I have to throw in another murder and get the heroine kidnapped again. It’s all very boring.’ (pages 110 – 111)

But back to the mystery, Mr Shaitana is murdered whilst his guests are playing bridge. Two games were set up – one made up of the four people he considered were murderers and the other in a separate room made up of the four detectives or investigators of crime. Mr Shaitana sat by the fire in the room with the murderers. When the four detectives finished their game they return to the other room where they find the game still in progress and Mr Shaitana still sitting by the fire – stabbed in the chest with an ornamental dagger.

What follows is that each detective carries out their own investigations and as I read I swung from one suspect to the other, but I was never really sure who the culprit was. Poirot is his usual brilliant self even though at one point he is astonished and upset at the possibility that he might be wrong:

‘Always I am right. It is so invariable that it startles me. But now it looks as though I am wrong. And that upsets me. (page 163)

But was he wrong?

I’ve read a lot of Agatha Christie’s books, most of which I’ve really enjoyed, but I’m not too keen on her books that involve spies and gangs of international criminals who are seeking world domination. And The Big Four, first published in 1927, is one of those books.

I’ve read a lot of Agatha Christie’s books, most of which I’ve really enjoyed, but I’m not too keen on her books that involve spies and gangs of international criminals who are seeking world domination. And The Big Four, first published in 1927, is one of those books. There are many things I like about

There are many things I like about  Third Girl

Third Girl