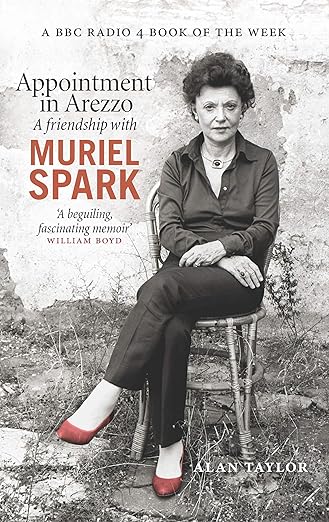

Travels with a Donkey in the Cévennes: A Journey of Solitude and Reflection by Robert Louis Stevenson, first published 1879

Namaskar Books| 2022| 124 pages| e-book| my own copy| 4*

The wild Cévennes region of France forms the backdrop for the pioneering travelogue Travels with a Donkey, written by a young Robert Louis Stevenson. Ever hopeful of encountering the adventure he yearned for and raising much needed finance at the start of his writing career, Stevenson embarked on the 120-mile, 12-day trek and recorded his experiences in this journal. His only companion for the trip was a predictably stubborn donkey called Modestine. Travels with a Donkey gives the reader a rare glimpse of the character of the author, and the journalistic and often comical style of writing is in refreshing contrast to Stevenson’s more famous works. (Goodreads)

This is a short nonfiction book, just right for both Nonfiction November and Novellas in November. It’s a book I’ve had since 2011 and I’m glad to say that it was well worth the wait. I enjoyed it on several levels, as travel writing, history of the Cévennes region, descriptive writing of the French countryside in 1878, observations of the local people and Stevenson’s thoughts on religion.

He began his journey through the Cévennes, a range of mountains in south-central France, at Le Monastier, a highland valley fifteen miles from Le Puy, where he spent a month preparing for his excursion southward to Alais (modern name, Alès) a distance of 120 miles.

I was struck by what he took with him – a sleeping sack, because he didn’t intend to rely on the hospitality of a village inn, and a tent was troublesome to pitch and then strike. Whereas, a sleeping sack was always ready to get into. His was extraordinary, made of green waterproof cart-cloth lined with blue ‘sheep’s fur’, nearly six feet square plus two triangular flaps to make a pillow at night and the top and bottom of the sack by day. It was a huge sort of long roll or sausage, large enough for two at a pinch. And that was why he bought a donkey from an old man. He called her Modestine because she was

a diminutive she-ass, not much bigger than a dog, the colour of a mouse, with a kindly eye and a determined under-jaw. There was something neat and high-bred, a quakerish elegance, about the rogue that hit my fancy on the spot.

But he soon discovered that unless he beat Modestine with a staff, which he didn’t want to do; it sickened him – and me too. He had to let her go at her own pace and patiently follow her and there were times when she just stopped and wouldn’t go any further. This was extremely slow and in the end he resorted to a goad, which was a plain wand with an eighth of an inch of pin which worked wonders on poor Modestine, who carried most of his equipment.

As well as his clothing, he also took his travelling wear of country velveteen, pilot coat and knitted spencer (a short waist-length, double-breasted, man’s jacket, originally named after George Spencer, 2nd Earl Spencer), some books, a railway rug, food, and a variety of other things including a revolver, a spirit lamp, lantern, candles, a jack-knife and large leather flask, a bottle of Beaujolais, a leg of cold mutton and a considerable quantity of black bread and white for himself and the donkey and of all things an eggbeater, which he later abandoned. He wasn’t travelling light!

The book is full of Stevenson’s descriptions of the countryside, such as this one of the landscape as he approached the Trappist Monastery of Our Lady of Sorrows:

The sun had come out as I left the shelter of a pine-wood, and I beheld suddenly a fine wild landscape to the south. High rocky hills, as blue as sapphires, closed the view, and between these lay ridge upon ridge, heathery, craggy, the sun glittering on veins of rock, the underwood clambering in the hollows, as rude as God made them at first.

Modestine had to stop at St Jean du Gard, as she just couldn’t travel any further and needed to rest. He sold her and continued on to Alais by diligence (a public stagecoach). He missed her after she was gone.

For twelve days we were fast companions; we had travelled upwards of a hundred and twelve miles, crossed several respectable ridges, and jogged along with our six legs by many a rocky and many a boggy road. After the first day, although sometimes I was hurt and distant in manner, I still kept my patience; and as for her, poor soul! she had come to regard me as a god. She loved to eat out of my hand. She was patient, elegant in form, the colour of an ideal mouse, and inimitably small.

And he wept!

I was rather surprised by how much I enjoyed this book, mainly because I didn’t know anything about it other than its title and thought it was perhaps fiction. Of course it isn’t and it’s full of detail of his hike that I haven’t mentioned in this review. I shouldn’t have been surprised as I’ve enjoyed other books by Stevenson – Treasure Island, Kidnapped and Catriona.

I read in Wikipedia that Stevenson’s purpose in making his journey ‘was designed to provide material for publication while allowing him to distance himself from a love affair with an American woman of which his friends and family did not approve and who had returned to her husband in California’, but without giving a source for this information. In his book Stevenson does say when talking to a monk he met at the Trappist Monastery that he was not a pedlar (as the monk thought), but a ‘literary man, who drew landscapes and was going to write a book’.