The Agatha Christie Reading Challenge is an open-ended challenge to read all of Agatha Christie’s books and short stories, run by Kerrie at Mysteries in Paradise. I first read some of Christie’s books when I was a teenager and hadn’t read any for years until I borrowed a copy of The Crooked House from my local library three years ago. This reminded me of how much I had enjoyed her books and set me off reading them again. Over the years I must have read a good number of them but had never kept any records of what I read at the time.

So when I saw that Kerrie was running this challenge I decided to join in. It’s one of the best challenges out, for me at least, because all you have to do is read Agatha Christie’s books at your own pace and link to the Agatha Christie Carnival once a month. There’s no pressure to meet any deadlines – if you haven’t read any Christie books for the Carnival that’s OK and you just carry on reading when you like.

I’m not even trying to read them in the order they were published, even though Kerrie and some others are, because I’m reading books I already own or books that I find in librarys and/or bookshops. So far I’ve read 17 and 2 collections of her short stories – I’ve listed them on a separate page.

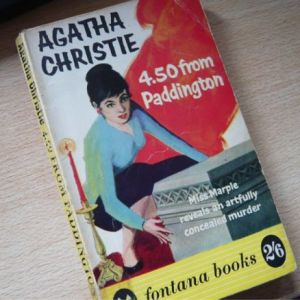

My latest find is 4.50 from Paddington, which I received from Juxtabook as part of my prize in her recent competition. Catherine described this book as a ‘rather aged paperback’ and it is, but then it is 50 years old, published in 1960 for just 2/6 (in old money). It may be old and faded, but because it was published soon after Agatha Christie wrote it, it has a contemporary feel about it. I’ve watched so many TV and film versions, with different actors playing the part of Miss Marple, some more successfully than others that it’s interesting to see this book. I’m not sure who the woman on the front cover is meant to portray – surely not Miss Marple?

And this is the back cover – really that’s all the blurb you need to capture your interest.

This will be my next Agatha Christie book to read.

Death on the Nile

Death on the Nile As she was writing this book at the time of her disappearance and divorce from her first husband, Archibald Christie it’s hardly surprising. It may not be her best book, but it’s still a good read. Ruth Kettering, the daughter of millionaire Rufus Van Aldin, is married to Derek, against her father’s advice. Agatha’s views on divorce are clear when Van Aldin tells Ruth she should divorce Derek, who he thinks is no good, rotten through and through and had only married her for her money, saying:

As she was writing this book at the time of her disappearance and divorce from her first husband, Archibald Christie it’s hardly surprising. It may not be her best book, but it’s still a good read. Ruth Kettering, the daughter of millionaire Rufus Van Aldin, is married to Derek, against her father’s advice. Agatha’s views on divorce are clear when Van Aldin tells Ruth she should divorce Derek, who he thinks is no good, rotten through and through and had only married her for her money, saying: