Week 2 in Novellas in November is Novellas in translation and a Maigret book is an obvious choice for me. But Maigret’s Memoirs is not your usual Maigret mystery. This a memoir written by Simenon writing as his fictional character, Maigret.

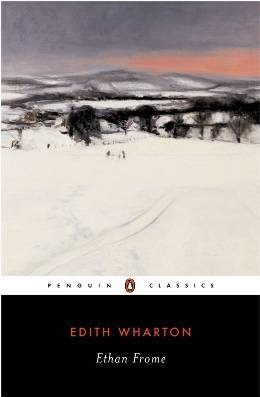

Penguin Classics| 2016| 160 pages| My Own Copy| 4*

I can still see Simenon coming into my office the next day, pleased with himself, displaying even more self-confidence, if possible, than before, but nevertheless with a touch of anxiety in his eyes.’

Maigret sets the record straight and tells the story of his own life, giving a rare glimpse into the mind of the great inspector – and the writer who would immortalise him.

‘One of the greatest writers of the twentieth century . . . Simenon was unequalled at making us look inside, though the ability was masked by his brilliance at absorbing us obsessively in his stories’ Guardian

‘A supreme writer . . . unforgettable vividness’ Independent

The original French version of Maigret’s Memoirs, Les Mémoires de Maigret, was first published in 1950. An English translation was later published in Great Britain in 1963. It is unlike any of the other Maigret novels. It’s a fictional autobiography by Georges Simenon writing as Maigret, beginning in 1927 or 1928 when Maigret and Simenon, calling himself Georges Sim, first ‘met’. I don’t recommend reading if you haven’t read some of the Maigret mysteries.

I enjoyed it – it’s a quick entertaining read as Maigret looks back to his first ‘meeting’ with Sim. He fills in some of the background of his early life and talks about his father and how he first met his wife, Louise. Simenon had written 34 Maigret novels before this one and Maigret took this opportunity to correct some of Simenon’s inaccuracies. I recognised some of the books – I’ve read 11 of his first 34 books.

One of the things that irritated Maigret the most was Simenon’s habit of mixing up dates, of putting at the beginning of his career investigations that had taken place later and vice versa. He’d kept press cuttings that his wife had collected and he had thought of using them to make a chronology of the main cases in which he’d been involved. And he also considered some details his wife had noted – concerning their apartment on Boulevard Richard Lenoir, pointing out that in several books Simenon had them living on Place des Vosges without explaining why. There were also times when he retired Maigret even though he was still several years away from retirement. Madame Maigret was also bothered by inaccuracies concerning other characters in the books and by Simenon’s description of a bottle of sloe gin that was always on the dresser in their apartment – that was in actual fact not sloe gin but raspberry liqueur given to them every year by her sister-in-law from Alsace.

Simenon drops facts and information piecemeal in his Maigret books and one thing I particularly like in Maigret’s Memoirs is that it is all about Maigret, but I did miss not having a mystery to solve.