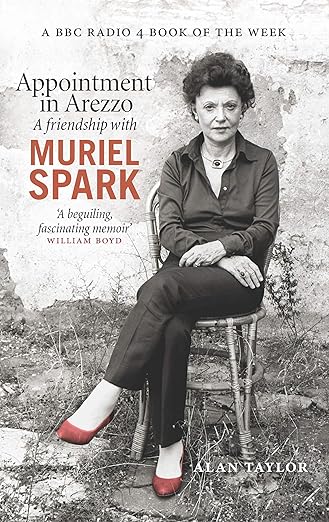

Appointment in Arezzo: A friendship with Muriel Spark by Alan Taylor

Polygon| 2017| 169| e-book| My own copy| 5*

Description:

This book is an intimate, fond and funny memoir of one of the greatest novelists of the last century. This colourful, personal, anecdotal, indiscreet and admiring memoir charts the course of Muriel Spark’s life revealing her as she really was. Once, she commented sitting over a glass of chianti at the kitchen table, that she was upset that the academic whom she had appointed her official biographer did not appear to think that she had ever cracked a joke in her life.

Alan Taylor here sets the record straight about this and many other things. With sources ranging from notebooks kept from his very first encounter with Muriel and the hundreds of letters they exchanged over the years, this is an invaluable portrait of one of Edinburgh’s premiere novelists. The book was published to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Muriel’s birth in 2018.

My thoughts:

This is a short nonfiction book of 169 pages on Kindle, so it’s just right for both Nonfiction November and Novellas in November. It’s a book I’ve had for a few years after a friend recommended it to me. I didn’t read it straight away because at the time the only book by Muriel Sparks I’d read was The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, which I loved. Since then I’ve read Loitering with Intent, (review to follow in due course), so I thought it was time I read Appointment in Arezzo.

Muriel Spark was born on 1 February 1918, in Edinburgh, the daughter of Bertie Camberg, a Jew who was born in Scotland and her mother, Sarah who was English and an Anglican. Alan Taylor touches on her early life and teenage years in Edinburgh in a middle -class enclave , where she attended James Gillespie’s High School for Girls – immortalised as Marcia Blaine School in The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie.

In July 1990 Alan Taylor first met Muriel Spark and her friend Penelope – Penny – Jardine in a hotel in Arezzo for dinner. The two women had shared a rambling house deep in the Val di Chiana 15 kilometres from Arezzo in Tuscany for twenty years. Penny is a sculptor who has exhibited at the Royal Academy in London; she supplied the domestic and business circumstances which allowed Muriel to flourish. Alan Taylor, a former deputy editor of The Scotsman and the founder-editor of the Scottish Review of Books, was there to interview her on the publication of her novel Symposium (1990). Their meeting led to a friendship and since then they met frequently during the last fifteen years of her life. She died at her home in Tuscany in April 2006 and is buried in the cemetery of Sant’Andrea Apostolo in Oliveto.

Following that first meeting, over the next fifteen years they met many times, when Taylor visited her in Tuscany, New York, London, Prague and finally in 2004 in Scotland and Edinburgh as well as exchanging many letters and telephone conversations. Taylor outlined details of her brief marriage in 1937 to Sidney Oswald Spark, which only lasted until 1940 when they separated, and about her son, Robin and their disagreement over her Jewishness. Robin believed that one must be either a Jew or a Gentile, whereas Muriel believed:

It was impossible ‘to separate’ the Jewess within her from the Gentile. In her mind, the two coexisted in harmony’ ‘uncomplainingly amongst one’s own bones’. Was she a Gentile? Or a Jewess? ‘Both and neither. What am I? I am what I am.

But Robin couldn’t cope with such ambiguity; he wanted certainty – in his mind one must be either Jew or Gentile. Their beliefs were irreconcilable. The full details are in Chapter 6, A Question of Jewishness.

Amongst many other topics they talked about her writing:

Fleur in Loitering with Intent spoke for her when she said: ‘I’ve come to learn for myself how little one needs, in the art of writing, to convey the lot, and how a lot of words, on the other hand, can convey so little. (page 17)

She had no idea when writing a book how it might turn out. Its theme built of itself and if it did not develop, it ramified. I wanted to know what she saw as her achievement, her legacy. ‘I have realised myself, ‘ she replied. ‘I have expressed something I brought into the world with me. I have liberated the novel in many ways, shown how anything whatever can be narrated, any experience set down, including sheer damn cheek. I think I have opened doors and windows in mind, and challenged fears – especially the most inhibiting fears about what a novel should be. (pages 98-99)

In a very real sense Muriel’s life is to be found in her work. She always said that if anyone wanted to know about the person behind the prose and poems they had only to read them closely and imaginatively. She is there, in the times and places and characters, in the choice of words and the construction of sentences, in the tone of voice, above all in the philosophy of existence. (pages 141-142)

There is so much more in this book. It is a fascinating insight into her life, and what she thought about writing, as well as reflecting on her books, as well as much more. I’ve really only touched the surface of this very readable book and I finished it knowing a lot more about Muriel Spark and her books – and keen to read more of them. And it’s illustrated with many photographs making it a warm, personal and affectionate account.